设计模式六大原则 单一职责原则 对象不应承担太多功能,正如一心不能而用,比如太多的工作(种类)会使人崩溃。唯有专注才能保证对象的高内聚;唯有唯一,才能保证对象的细粒度。

解决问题:

假如有A和B两个类,当A需求发生改变需要修改时,不能导致B类出问题。

现状:

在实际情况很难去做到单一职责原则,因为随着业务的不断变更,类的职责也在发生着变化,即职责扩散。如类A完成职责P的功能,但是随着后期业务细化,职责P分解成更小粒度的P1与P2,这时根据单一职责原则则需要拆分类A以分别满足细分后的职责P1和P2。但是实际开发环节,若类的逻辑足够简单,可以在代码上级别上违背单一职责原则;若类的方法足够少,可以在方法级别上违背单一职责原则。

经典案例:

用一个类描述动物呼吸的场景

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 class Animal public void breath (String animal) System.out.println(animal + "呼吸空气" ); } } class Program public static void main (String[] args) Animal animal = new Animal(); animal.breath("🐂" ); animal.breath("🐖" ); animal.breath("🐎" ); animal.breath("🐟" ); } }

从示例可以发现,Animal类已不足以支持客户端所需职责,因为🐟吃水。若遵循单一职责原则,则需要拆分Animal类。

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 class Animal public void breath (String animal) System.out.println(animal + "呼吸空气" ); } } class Aquatic public void breath (String animal) System.out.println(animal + "吃水" ); } } class Program public static void main (String[] args) Animal animal = new Animal(); animal.breath("🐂" ); animal.breath("🐖" ); animal.breath("🐎" ); Aquatic aquatic = new Aquatic(); aquatic.breath("🐟" ); } }

这时你会发现,若针对简单的业务逻辑来说,若每次细分都需要拆分的话实在是太繁琐了,而且服务端与客户端代码都需要做相应的修改。所以直接在原先类中进行修改,虽然违背了单一职责原则,但花销小。

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 class Animal public void breath (String animal) if ("🐟" .equals(animal)) { System.out.println(animal + "呼吸空气" ); } else { System.out.println(animal + "吃水" ); } } }

优点:

降低类的功能复杂度

提高系统的可维护性

变更风险低

接口隔离原则

客户端不应依赖它不需要的接口

类间的依赖关系应该建立在最小的接口上

其实通俗来理解就是,不要在一个接口里面放很多的方法,这样会显得这个类很臃肿。接口应该尽量细化,一个接口对应一个功能模块,同时接口里面的方法应该尽可能的少,使接口更加灵活轻便。或许有的人认为接口隔离原则和单一职责原则很像,但两个原则还是存在着明显的区别。单一职责原则是在业务逻辑上的划分,注重的是职责。接口隔离原则是基于接口设计考虑。例如一个接口的职责包含10个方法,这10个方法都放在同一接口中,并且提供给多个模块调用,但不同模块需要依赖的方法是不一样的,这时模块为了实现自己的功能就不得不实现一些对其没有意义的方法,这样的设计是不符合接口隔离原则的。接口隔离原则要求”尽量使用多个专门的接口”专门提供给不同的模块。

经典案例:

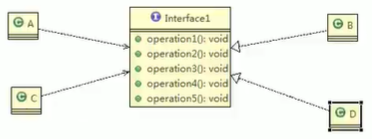

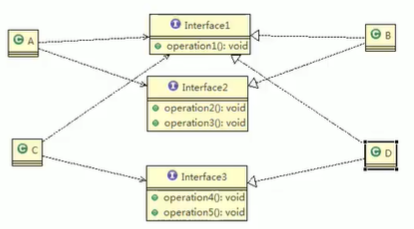

类A通过Interface1依赖类B,1,2,3;类B通过Interface1依赖D,1,4,5。

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 class Program public static void main (String[] args) A a = new A(); B b = new B(); a.use1(b); a.use2(b); a.use3(b); } } interface interface1 void operation1 () void operation2 () void operation3 () void operation4 () void operation5 () } class B implements interface1 @Override public void operation1 () System.out.println("B->{nameof(operation1)}" ); } @Override public void operation2 () System.out.println("B->{nameof(operation2)}" ); } @Override public void operation3 () System.out.println("B->{nameof(operation3)}" ); } @Override public void operation4 () System.out.println("B->{nameof(operation4)}" ); } @Override public void operation5 () System.out.println("B->{nameof(operation5)}" ); } } class D implements interface1 @Override public void operation1 () System.out.println("D->{nameof(operation1)}" ); } @Override public void operation2 () System.out.println("D->{nameof(operation2)}" ); } @Override public void operation3 () System.out.println("D->{nameof(operation3)}" ); } @Override public void operation4 () System.out.println("D->{nameof(operation4)}" ); } @Override public void operation5 () System.out.println("D->{nameof(operation5)}" ); } } class A public void use1 (interface1 interface1) interface1.operation1(); } public void use2 (interface1 interface1) interface1.operation1(); } public void use3 (interface1 interface1) interface1.operation1(); } } class C public void use1 (interface1 interface1) interface1.operation1(); } public void use2 (interface1 interface1) interface1.operation1(); } public void use3 (interface1 interface1) interface1.operation1(); } }

显然,上述设计不符合接口隔离原则。

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 class Program public static void main (String[] args) A a = new A(); B b = new B(); a.use1(b); a.use2(b); a.use3(b); } } interface interface1 void operation1 () } interface interface2 void operation2 () void operation3 () } interface interface3 void operation4 () void operation5 () } class B implements interface1 ,interface2 @Override public void operation1 () System.out.println("B->{nameof(operation1)}" ); } @Override public void operation2 () System.out.println("B->{nameof(operation2)}" ); } @Override public void operation3 () System.out.println("B->{nameof(operation3)}" ); } } class D implements interface1 ,interface3 @Override public void operation1 () System.out.println("D->{nameof(operation1)}" ); } @Override public void operation4 () System.out.println("D->{nameof(operation4)}" ); } @Override public void operation5 () System.out.println("D->{nameof(operation5)}" ); } } class A public void use1 (interface1 interface1) interface1.operation1(); } public void use2 (interface2 interface2) interface2.operation2(); } public void use3 (interface2 interface2) interface2.operation3(); } } class C public void use1 (interface1 interface1) interface1.operation1(); } public void use4 (interface3 interface3) interface3.operation4(); } public void use5 (interface3 interface3) interface3.operation5(); } }

依赖倒置原则

经典案例:

三二班有个小明,想要学习JAVA,于是买了本《深入理解JAVA》进行学习。

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 class Program public static void main (String[] args) XiaoMing xm = new XiaoMing(); xm.Study(new CSharp()); } } class CSharp public void ShowMsg () System.out.println("《深入理解JAVA》" ); } } class XiaoMing public void Study (CSharp cSharp) cSharp.ShowMsg(); } }

过了一段时间,小明觉得光学习一门太没有意思了。听说Linux比较好玩,于是买了本《鸟哥的私房菜Linux》。

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 class Program public static void main (String[] args) XiaoMing xm = new XiaoMing(); xm.Study(new CSharp()); xm.Study(new Linux()); } } class CSharp public void ShowMsg () System.out.println("《深入理解JAVA》" ); } } class Linux public void ShowMsg () System.out.println("《鸟哥的私房菜Linux》" ); } } class XiaoMing public void Study (CSharp cSharp) cSharp.ShowMsg(); } public void Study (Linux linux) linux.ShowMsg(); } }

小明是一个聪明的娃,过了一段时间学得差不多了,于是又想学习《设计模式》…就这样小明在不断学习中成长,而我们的代码却越来越臃肿,变得难以维护。由于XiaoMing是一个高级模块并且是一个细节实现类,此类依赖了书籍CSharp和Linux又是一个细节依赖类,这导致XiaoMing每读一本书都需要修改代码,这与我们的依赖倒置原则是相悖的。那如何解决XiaoMing的这种问题呢?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 class Program public static void main (String[] args) XiaoMing xm = new XiaoMing(); xm.Study(new CSharp()); xm.Study(new Linux()); } } interface IBook void ShowMsg () } class CSharp implements IBook @Override public void ShowMsg () System.out.println("《深入理解JAVA》" ); } } class Linux implements IBook @Override public void ShowMsg () System.out.println("《鸟哥的私房菜Linux》" ); } } class XiaoMing public void Study (IBook book) book.ShowMsg(); } }

我们发现,只要让XiaoMing依赖于抽象IBook,其他书籍依赖于该抽象,以后不管小明读什么书,哈哈都是so easy的。

依赖关系传递的三种方式:

1、通过接口传递(上述示例)

1 2 3 4 5 class XiaoMing public void Study (IBook book) book.ShowMsg(); } }

2、通过构造方法传递

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 class XiaoMing private IBook _book; public XiaoMing (IBook book) this ._book = book; } public void Study () this ._book.ShowMsg(); } }

3、通过Setter方法传递

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 class XiaoMing private IBook _book; public void setBook (IBook book) this ._book = book; } public void Study () this ._book.ShowMsg(); } }

依赖倒置原则的本质就是通过抽象(接口或抽象类)使各个类或模块的实现彼此独立,不互相影响,实现模块间的松耦合。我们在项目中使用这个原则要遵循下面的规则:

里氏替换原则 子类应当可以替换父类并出现在父类能够出现的地方。比如:公司搞年度派对,都有员工都可以抽奖,那么不管是新员工还是老员工,也不管是总部员工还是外派员工,都应当可以参加抽奖。

里氏替换至少包含一下两个含义:

里氏替换原则是针对继承而言的,如果继承是为了实现代码重用,也就是为了共享方法,那么共享的父类方法就应该保持不变,不能被子类重新定义。子类只能通过新添加方法来扩展功能,父类和子类都可以实例化,而子类继承的方法和父类是一样的,父类调用方法的地方,子类也可以调用同一个继承得来的,逻辑和父类一致的方法,这时用子类对象将父类对象替换掉时,当然逻辑一致,相安无事。

如果继承的目的是为了多态,而多态的前提就是子类覆盖并重新定义父类的方法,为了符合LSP,我们应该将父类定义为抽象类,并定义抽象方法,让子类重新定义这些方法,当父类是抽象类时,父类就是不能实例化,所以也不存在可实例化的父类对象在程序里。也就不存在子类替换父类实例(根本不存在父类实例了)时逻辑不一致的可能。

案例:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 class Program public static void main (String[] args) A a = new A(); System.out.println("100-50=" +a.func1(100 , 50 )); B b = new B(); System.out.println("100-50=" +b.func1(100 , 50 )); System.out.println("100-50=" +b.func2(100 , 50 )); } } class A public int func1 (int num1, int num2) return num1 - num2; } } class B extends A public int func2 (int num1, int num2) return func1(num1, num2) + 100 ; } }

由上述代码可以看出,若类B在继承类A时不注意,重写了父类方法func1就会导致结果与预想的不一致,改变了父类原有的功能。

故里氏转换原则应满足以下要求:

子类可以实现父类的抽象方法,但不能覆盖父类的非抽象方法

子类可以增加自己特有的方法

当子类的方法重载父类的方法时,方法的形参要比父类方法的输入参数更宽松

当子类的方法实现父类的抽象方法时,方法的返回值应比父类更严格

优点:

可以大大减少程序的bug以及增强代码的可读性

迪米特法则 也叫最少知识原则。迪米特法则的定义是只与你的直接朋友交谈,不与”陌生人”说话。如果两个软件实体无须直接通信,那么就不应当发生直接的相互调用,可以通过第三方转发该应用。其目的是降低类之间的耦合度,提高模块的相对独立性。

迪米特法则中的朋友是指:当前对象本身、当前对象的成员对象、当前对象所创建的对象、当前对象的方法参数等,这些对象存在关联、聚合或组合关系,可以直接访问这些对象的方法。

优点:

缺点:

过度使用迪米特法则会使系统产生大量的中介类,从而增加系统的复杂性,使模块之间的通信效率降低。所以,在釆用迪米特法则时需要反复权衡,确保高内聚和低耦合的同时,保证系统的结构清晰。

使用迪米特法则需要注意:

在类的划分上,应该创建弱耦合的类。类与类之间的耦合越弱,就越有利于实现可复用的目标。

在类的结构设计上,尽量降低类成员的访问权限。

在类的设计上,优先考虑将一个类设置成不变类。

在对其他类的引用上,将引用其他对象的次数降到最低。

不暴露类的属性成员,而应该提供相应的访问器(set 和 get 方法)。

谨慎使用序列化(Serializable)功能。

经典案例:

蔡徐坤与经纪人的关系实例。蔡徐坤只负责浪,经纪人负责处理日常事务,如与粉丝的见面会,与媒体公司的业务洽淡等。

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 class Program public static void main (String[] args) Agent agent = new Agent(); agent.setStar(new Star("蔡徐坤" )); agent.setFans(new Fans("小明" )); agent.setCompany(new Company("**公司" )); agent.meeting(); agent.business(); } } class Agent private Star myStar; private Fans myFans; private Company myCompany; public void setStar (Star myStar) this .myStar = myStar; } public void setFans (Fans myFans) this .myFans = myFans; } public void setCompany (Company myCompany) this .myCompany = myCompany; } public void meeting () System.out.println(myFans.getName()+"与明星" +myStar.getName()+"见面了。" ); } public void business () System.out.println(myCompany.getName()+"与明星" +myStar.getName()+"洽谈业务。" ); } } class Star private string name; public Star (string name) this .name = name; } public string getName () return this .name; } } class Company private string name; public Company (string name) this .name = name; } public string getName () return this .name; } } class Fans private string name; public Fans (string name) this .name = name; } public string getName () return this .name; } }

开闭原则 软件对象(类、模块、方法等)应该对于扩展是开放的,对修改是关闭的。比如:一个网络模块,原来只有服务端功能,而现在要加入客户端功能,那么应当在不用修改服务端功能代码的前提下,就能够增加客户端功能的实现代码,这要求在设计之初,就应当将客户端和服务端分开。公共部分抽象出来。

问题由来:

在软件的生命周期内,因为变化、升级和维护等原因需要对软件原有代码进行修改时,可能会给旧代码中引入错误,也可能会使我们不得不对整个功能进行重构,并且需要原有代码经过重新测试。

解决办法:

当软件需要变化时,尽量通过扩展软件实体的行为来实现变化,而不是通过修改已有的代码来实现变化。

开闭原则是面向对象设计中最基础的设计原则,它指导我们如何建立稳定灵活的系统。开闭原则可能是设计模式六项原则中定义最模糊的一个了,它只告诉我们对扩展开放,对修改关闭,可是到底如何才能做到对扩展开放,对修改关闭,并没有明确的告诉我们。以前,如果有人告诉我”你进行设计的时候一定要遵守开闭原则”,我会觉的他什么都没说,但貌似又什么都说了。因为开闭原则真的太虚了。

在仔细思考以及仔细阅读很多设计模式的文章后,终于对开闭原则有了一点认识。其实,我们遵循设计模式前面5大原则,以及使用23种设计模式的目的就是遵循开闭原则。也就是说,只要我们对前面5项原则遵守的好了,设计出的软件自然是符合开闭原则的,这个开闭原则更像是前面五项原则遵守程度的”平均得分”,前面5项原则遵守的好,平均分自然就高,说明软件设计开闭原则遵守的好;如果前面5项原则遵守的不好,则说明开闭原则遵守的不好。

其实笔者认为,开闭原则无非就是想表达这样一层意思:用抽象构建框架,用实现扩展细节。因为抽象灵活性好,适应性广,只要抽象的合理,可以基本保持软件架构的稳定。而软件中易变的细节,我们用从抽象派生的实现类来进行扩展,当软件需要发生变化时,我们只需要根据需求重新派生一个实现类来扩展就可以了。当然前提是我们的抽象要合理,要对需求的变更有前瞻性和预见性才行。

说到这里,再回想一下前面说的5项原则,恰恰是告诉我们用抽象构建框架,用实现扩展细节的注意事项而已:单一职责原则告诉我们实现类要职责单一;里氏替换原则告诉我们不要破坏继承体系;依赖倒置原则告诉我们要面向接口编程;接口隔离原则告诉我们在设计接口的时候要精简单一;迪米特法则告诉我们要降低耦合。而开闭原则是总纲,他告诉我们要对扩展开放,对修改关闭。

为什么使用开闭原则?

如何使用开闭原则?

抽象约束

抽象对一组事物的通用描述,没有具体的实现,也就表示它可以有非常多的可能性,可以跟随需求的变化而变化。因此,通过接口或抽象类可以约束一组可能变化的行为,并且能够实现对扩展开放。

元数据控件模块行为

制定项目章程

封装变化

将相同的变化封装到一个接口或抽象类中,将不同的变化封装到不同的接口或抽象类中,不应该有两个不同变化出现在同一个接口或抽象类中。

案例:

一个工厂生产宝马和奥迪两种品牌的车

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 class Program public static void main (String[] args) AutomobileFactory carf = new AutomobileFactory(); carf.createAuto(AutomobileFactory.AutoType.BMW); carf.createAuto(AutomobileFactory.AutoType.AUDI); } } interface IAutomobile } class Audi implements IAutomobile public Audi () System.out.println("hi 我是奥迪" ); } } class BMW implements IAutomobile public Audi () System.out.println("hello 我是宝马" ); } } class AutomobileFactory public enum AutoType AUDI, BMW } public IAutomobile createAuto (AutoType carType) switch (carType) { case AutoType.AUDI: return new Audi(); case AutoType.BMW: return new BMW(); } return null ; } }

随着业务不断扩展,需要生产宾利,怎么办?对原有工厂进行改造使其满足生产宾利的条件?对开闭原则来说,这显然不合适。于是。。。

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 class Program public static void main (String[] args) IAutomobileFactory audi = new AudiFactory(); audi.createAuto(); IAutomobileFactory bmw = new BMWFactory(); bmw.createAuto(); } } interface IAutomobile } class Audi implements IAutomobile public Audi () System.out.println("hi 我是奥迪" ); } } class BMW implements IAutomobile public Audi () System.out.println("hello 我是宝马" ); } } interface IAutomobileFactory IAutomobile createAuto () ; } class AudiFactory implements IAutomobileFactory public IAutomobile createAuto () return new Audi(); } } class BMWFactory implements IAutomobileFactory public IAutomobile createAuto () return new BMW(); } }